The fluid path includes everything from the vessel that contains the liquid all the way to the point of dispense. It is only the beginning once the preliminary specifications of the fluid path have been determined. Through our understanding of fluid dynamics and our experience in micro volume dispensing we optimise components and tuning of the control system to maximise your system performance.

If you want to optimise your manufacturing process to Increase Yield while Reducing Defects, Downtime, Costs and Waste, contact us

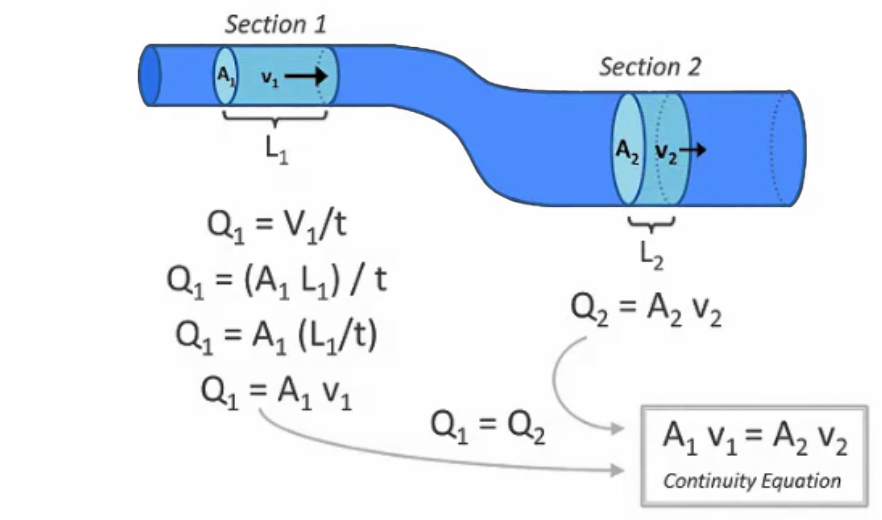

Many factors influence Fluid Dynamics. Here follows a brief explanation of some of the key elements and principles that govern fluid behaviour we consider when designing and building microvolume dispensing systems.

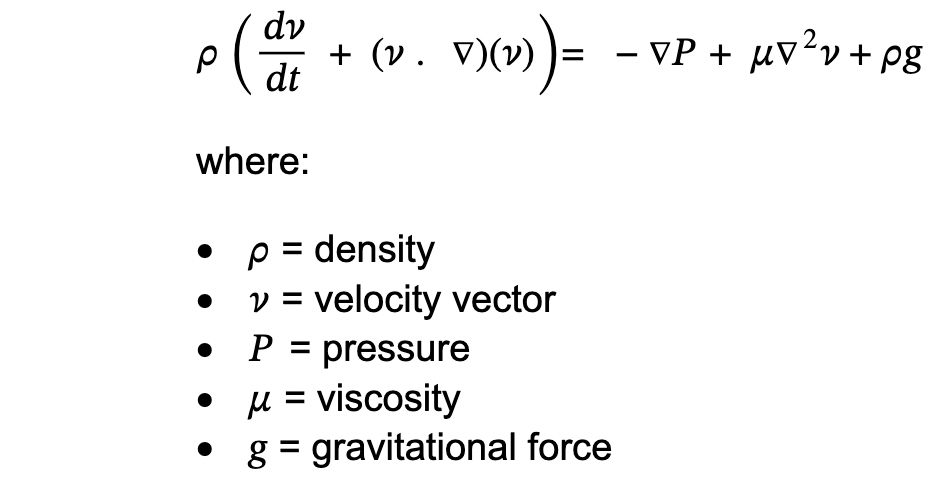

Describes how forces (pressure, viscosity, and external forces) affect fluid motion.

Based on Newton’s Second Law: F = ma

General Form:

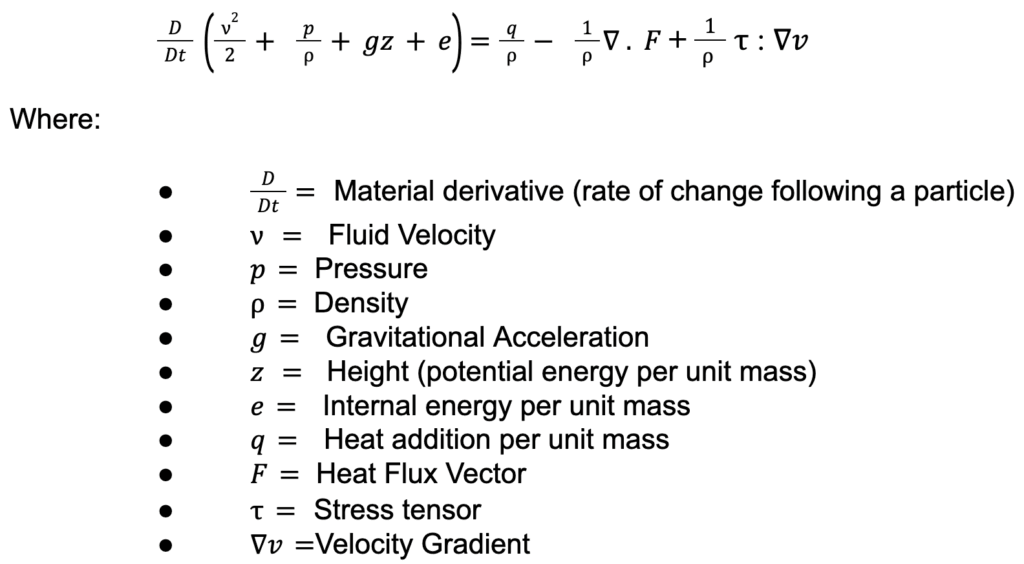

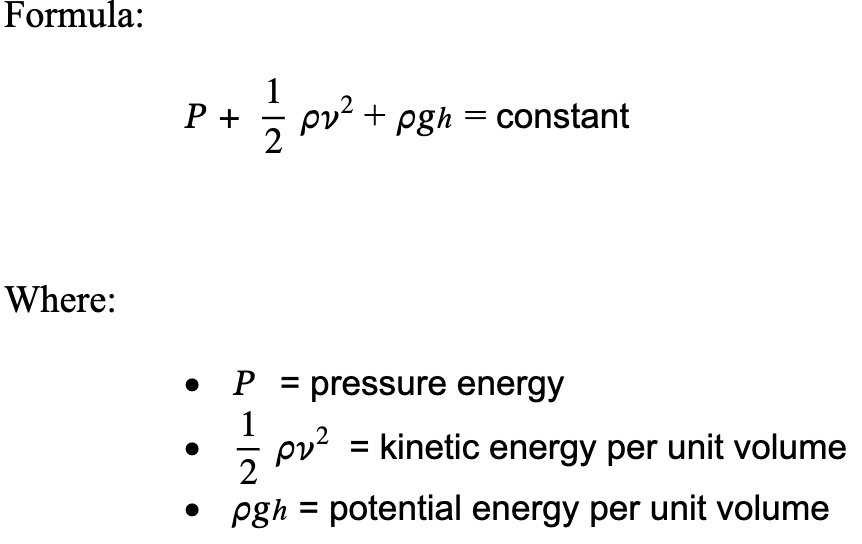

The energy equation in fluid dynamics is a mathematical representation of the conservation of energy principle, specifically applied to fluid flow. It accounts for how energy is transferred within a fluid system due to work done, heat transfer, and internal energy changes.

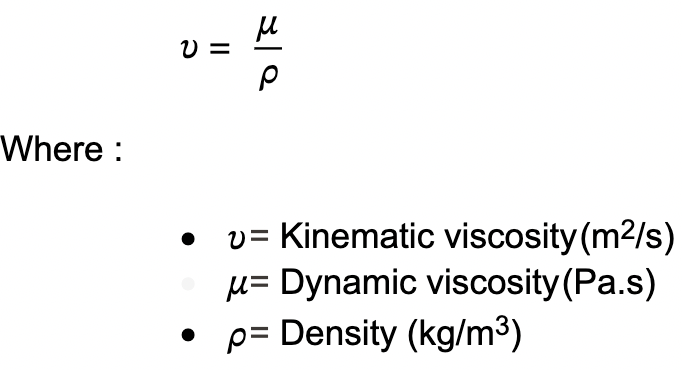

Viscosity (𝜇) is a measure of a fluid’s resistance to deformation or flow due to internal friction between its layers. It plays a crucial role in fluid dynamics, particularly in the Navier-Stokes equations (Momentum Equations) and the analysis of laminar and turbulent flow.

The relationship between viscosity and shear rate (also called the shear rate or flow rate) is central to understanding the flow behaviour of fluids.

Here’s how they interact:

The relationship between viscosity and shear rate can vary depending on the type of fluid:

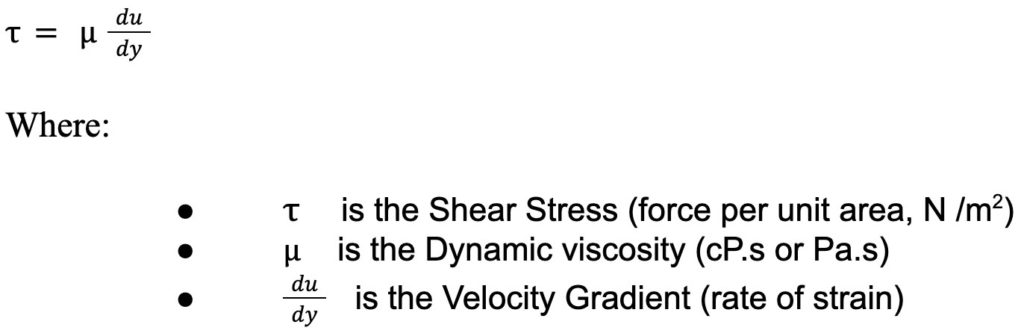

5a Newtonian Fluids (such as water, honey and air) follow Newton’s Law of Viscosity which details the linear relationship between shear stress (𝜏) and velocity gradient (𝑑𝑢/𝑑𝑦), represented by the formula:

This equation states that shear stress is directly proportional to the rate of strain, with viscosity a(μ) acting as the proportionality constant.

Newtonian fluids (like Water, Honey, Silicone Oils or Air), behave predictably, and changes in shear rate do not alter the viscosity.

Unfortunately, the majority of fluids do not exhibit Newtonian behaviour and an understanding of their Rheology is required to predict and control their flow behaviour.

5.b Non-Newtonian Fluids

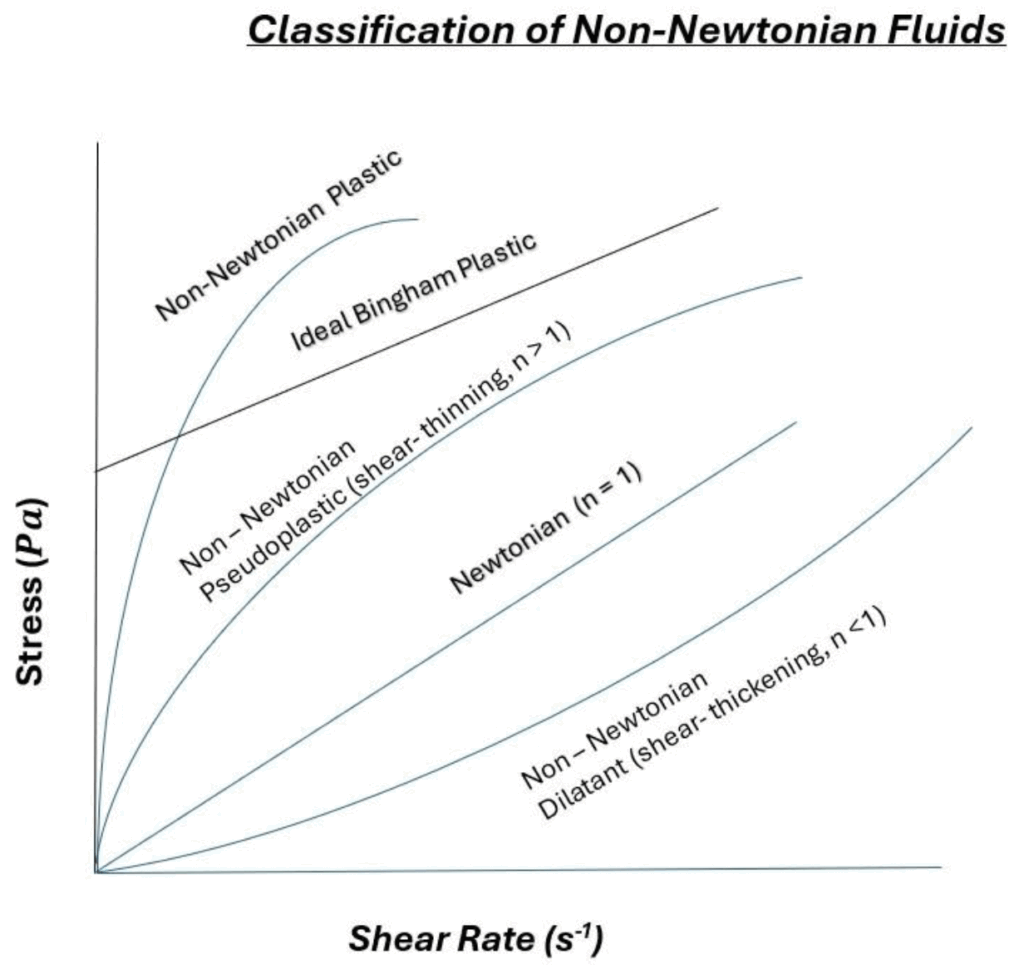

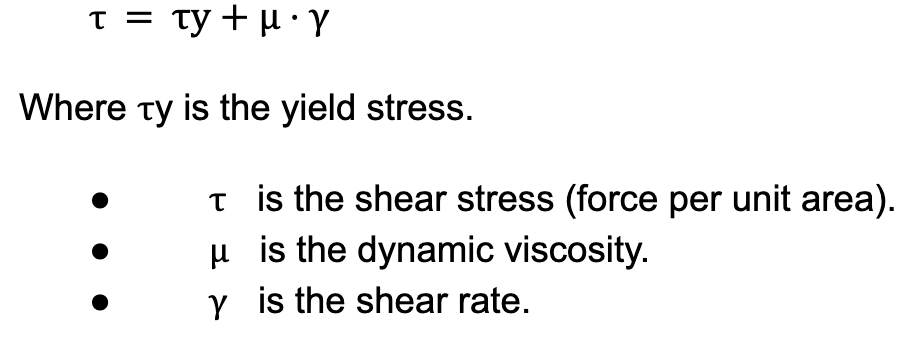

Viscosity appears explicitly in the Navier-Stokes equations, which aNon-Newtonian fluids, like ketchup or blood, exhibit a variable viscosity depending on the shear rate. This means that the viscosity can change as the fluid is subjected to different shear rates.

There are several types of Non-Newtonian behaviour:

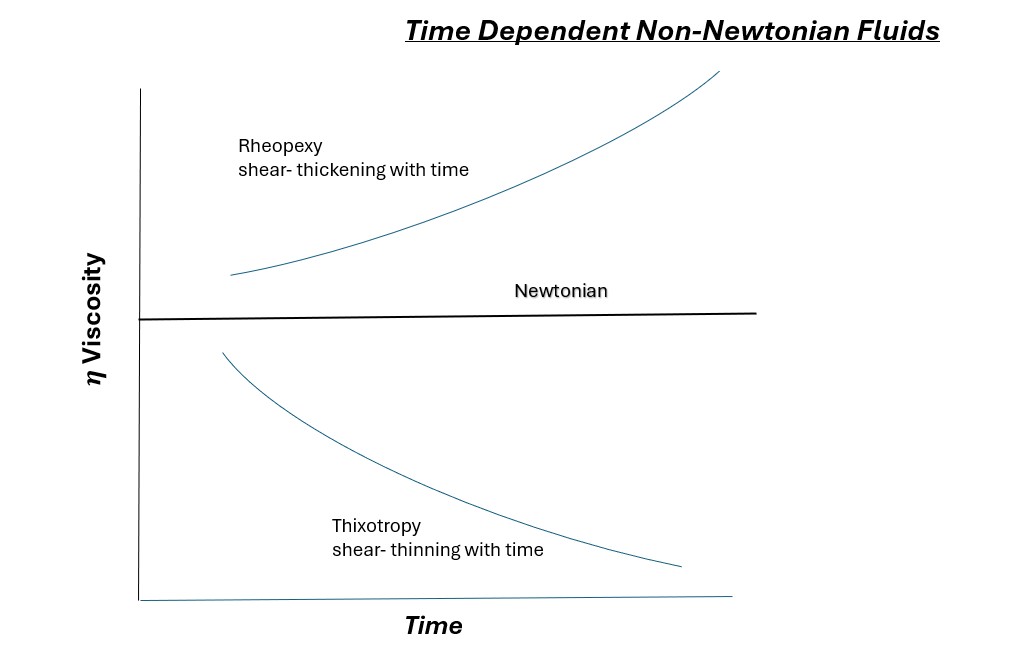

Other Non-Newtonian behaviours are Time Dependent.

Under conditions of constant shear rate some fluids will display a change in viscosity with time.

There are two categories to consider:

Both thixotropy and rheopexy may occur in combination with any of the previously discussed flow behaviours, or only at certain shear rates.

The time element is extremely variable; under conditions of constant shear, some fluids will reach their final viscosity value in a few seconds, while others may take up to several days.

Rheopectic fluids are rarely encountered. Thixotropy, however, is frequently observed in materials such as greases, heavy printing inks, and paints.

Because of the range of behaviours multiple models are required to Characterise Non-Newtonian Fluid behaviour.

The Power Law fluid model is the simplest and perhaps most commonly employed model. It gives a basic relation for viscosity, 𝜈, and the shear rate, 𝛾. In this model, the value of viscosity can be bounded by a lower bound value, 𝜈 min, and an upper bound value, 𝜈 max.

A limitation of the Power Law Model is that it is only valid over a limited range of Shear rates. As required this can be addressed by utilising Bird-Carreau and Cross-Power Law models to cover the entire Shear Rate Range. The Herschel–Bulkley model is also used to evaluate non-Newtonian fluids. This model combines the behaviour of Bingham and power-law fluids in a single relation.

Summary:

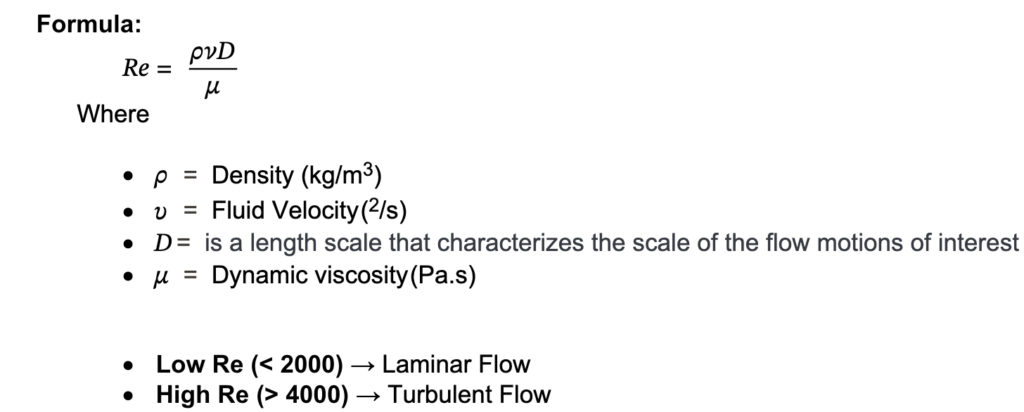

The Reynolds number (Re) is a dimensionless quantity (no unit of measure) in fluid dynamics that predicts whether fluid flow is laminar or turbulent. It represents the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces within a fluid. A low Reynolds number indicates laminar flow (smooth, predictable), while a high Reynolds number suggests turbulent flow (chaotic, unpredictable).

In designing or optimizing a micro dispensing system, our focus is on controlling boundary layer effects and avoiding turbulence to ensure high accuracy, repeatability, and consistency.

Get in touch with us below to get started. Feel free to call us on +353 (0)46 900 9050 or email

info@industrial-fluidics.com

Get in touch with us below to get started. Feel free to call us on

+353 (0)46 900 9050 or email

info@industrial-fluidics.com

"*" indicates required fields

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |